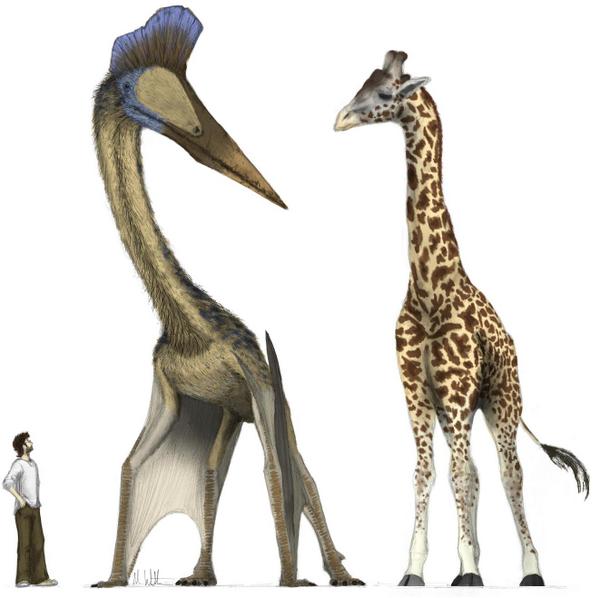

One of the largest pterosaurs, or flying reptiles, ever to flutter above the prehistoric skies was the Quetzalcoatlus. When resting, this giant of the clouds was taller than a modern-day giraffe, and considerably stronger. Tearing through the air at 130 kilometres per hour, Quetzalcoatlus was said to be fond of snacking on juvenile dinosaurs that strayed too far from their parents, while its smaller flying cousins, the pterodactyls, settled for fish. Its height met it could very easily look a giraffe in the eye, which may well be an unpleasant experience for the giraffe.

With a wing-span of around fifteen metres, half the length of a red London bus, Quetzalcoatlus may well have been the largest flying reptile, and indeed the largest flying animal full-stop, of all time. Compare Quetzalcoatlus’ over 30 feet wingspan with the world’s current largest flying bird, the Andean condor, whose span reaches about 10 feet, and you can readily appreciate how a flock of Quetzalcoatlus would have easily darkened the sky as they flew above you. Despite these astonishing bodily proportions, this pterosaur is considerably less well known outside the palaeontologist community.

Quetzalcoatlus was named by its discoverers in honour of the Aztec feathered-serpent god Quetzalcoatl and is believed to have weighed close to 100 kilograms, necessitating its plane like wingspan. It was one of the last prehistoric reptile species known from the fossil record and disappeared during the great Cretaceous extinction of 65 million years ago, which most scientists believed was caused by a meteor or comet slamming into the Yucatan peninsula in now what is known as Mexico. Like other prehistoric reptiles, Quetzalcoatlus was a victim of the collapse of food chains that occurred in the millennia after this cataclysm. The species is said to have existed for around five million years before its demise. Its remains were first discovered by Douglas Lawson from the Maastrichtian Javelina Formation, a fossil bed located in Big Bend National Park of Texas, United States of America in 1971, although extensive interest in the wider community and the media did not take off until three decades later. Interestingly, the reptile’s remains were not found in fossilised marine sediments like others of its family, such as Pterodactyl, who would travel miles out to sea to hunt. Instead Lawson, who was a geology student at that time at the University of Texas-Austin, unearthed Quetzalcoatlus in the preserved remains of a river bed, which intrigued many palaeontologists trying to unmask the lifestyle and feeding habits of this unique and fearsome creature.

Like other pterosaurs, which also had phenomenal wingspans, Quetzalcoatlus could stay airborne due to the aerodynamics of its leathery wings, which worked rather like those of a glider aircraft, but also because its skeleton was lighter than that of land-based dinosaurs. The bones were spongy and contained large air pocket to help reduce drag while in the air, a trait shared with modern birds, who some scientist believe are descendants of smaller flying relatives of Quetzalcoatlus. They were estimated to glide at elevations of 10,000 to 15,000 feet with very minimal movement of its tarpaulin-like wings to save on expending energy. It controlled its flight movement by swivelling and adjusting its flexible wing tips and flexing the three fingers on the wing’s leading edge – along with subtle head movements to alter the flow of air over its body while soaring above the marshy swamps and grasslands of the prehistoric US and Canadian east coasts.

Even with its aerodynamics, flight take-off must have been a lot of work for Quetzalcoatlus. As it lived millions of years ago, there is no way of determining exactly how it took to the skies and glided (not actually fly, as modern birds generally do). An analysis of the animal’s remains suggest that it had to run across the ground for a distance before catching the wind and soaring up above, as a plane must use a runway in order to gain traction for flight. That analysis suggested that Quetzalcoatlus used all four of its limbs to help it get airborne. Its heavily-muscled front legs helped it vault into the air, while the back legs, which were more lean and spindly, played a secondary support role, and were more necessary for when the pterosaur was walking on land. Some hypothesise that Quetzalcoatlus made life easier on itself by launching itself off the tops of sheer cliffs and exploiting thermals of warm air rising from the sea’s surface.

Quetzalcoatlus was built not only for flight, but also for the kill – at least as some scientists surmise. With an elongated neck, rather like the giraffe in the artist’s impression above, the pterosaur could see for metres around as it searched for prey in the grasslands of prehistoric North America. Its bill was also extremely lengthy and robust and it had no problem with picking up smaller dinosaurs and devouring them. It even was believed to have used its jaws to impale some prey as it hunted them. Some scientists think that Quetzalcoatlus was rather more like a giant prehistoric vulture, using the bill to pick the rotting flesh from corpses or the abandoned kills of other carnivorous dinosaurs. A clip from a BBC documentary on flying reptiles shows that Quetzalcoatlus searched the ground for recently slaughtered dinosaurs and used its jaws to tear chunks from the carcass, but also capable of swallowing whole smaller live prey that dared to get in the way. Its discovery near an inland river also suggests that Quetzalcoatlus’ diet was not much different from its coastal relatives, and that it subsisted on a diet of molluscs and crustaceans, using its beak to probe the sands for burrowed prey much like the oystercatchers seen on our modern beaches. Alternatively it may have behaved as a seagull, fluttering just above the warm shallow seas of the late Cretaceous and plucking fish from just below the waves. No-one is one hundred per cent sure.

It was a member of the Azhdarchidae, a family of advanced toothless pterosaurs with unusually long, stiffened necks. Members of this branch of the reptilian kingdom occurred all over the Americas. Among palaeontologists and the wider prehistoric literature, it is known as a pterodactyloid pterosaur, due to the long ‘dactyls’ (fingers) it possessed. Its full Latin name was Queztalcoatlus northropi. In addition to the nod to the Aztec religion, the formal name also honours John Knudsen Northrop, the founder of the Northrop aviation company, who was interested in large tailless aircraft designs resembling Quetzalcoatlus. The earliest known pterosaurs lived about 220 million years ago in the Triassic period. They were the first vertebrates to achieve the use of daily flight, a legacy now evident in bats and birds. Quetzalcoatlus, if alive today, may well have made the skies more hazardous to human airborne traffic, but would have inspired awe and profound respect (and possibly a great deal of fear) among the ant-like humans that it saw milling across the ground from its vantage point thousands of metres in the skies above.

SOURCES:

Half-Eaten Mind, Twitter https://twitter.com/halfeatenmind

Gautam Trivedi , Twitter https://twitter.com/Gotham3

“DINO FACT FILE – QUETZALCOATLUS, ABC/BBC, Australian Broadcasting Corporation http://www.abc.net.au/dinosaurs/fact_files/volcanic/quetzalcoatlus.htm

“Quetzalcoatlus” – Bob Strauss, About.com – Education – Dinosaurs http://dinosaurs.about.com/od/aviandinosaurs3/p/quetzalcoatlus.htm

“10 Facts About Quetzalcoatlus Everything You Need to Know About the World’s Biggest Pterosaur” Bob Strauss, About.com – Education – Dinosaurs http://dinosaurs.about.com/od/otherprehistoriclife/a/Quetzalcoatlus-Facts.htm

“Quetzalcoatlus” – Wikia Dinopedia http://dinosaurs.wikia.com/wiki/Quetzalcoatlus

“QUETZALCOATLUS” – ZoomDinosaurs.com Dinosaur and Paleontology Dictionary, EnchantedLearning.com http://www.enchantedlearning.com/subjects/dinosaurs/dinos/Quetzalcoatlus.shtml

“Pterosaurs” – Big Bend National Park Texas, National Park Service/United States Department of the Interior http://www.nps.gov/bibe/naturescience/pterosaur.htm

IMAGE CREDIT:

Gautam Trivedi , Twitter https://twitter.com/Gotham3

VIDEO CREDIT:

“Quetzalcoatlus – Flying monsters” – Paleo Studio (via ‘Flying Monsters’ series from the BBC), YouTube GB (29 December 2013) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sAQX6RbtjFg

This is so interesting, thank you for sharing and visiting my blog, Namaste, Cheryl-Lynn

LikeLike

My pleasure and namaskar!

Vijay

LikeLike

I did not know your Angel writer who passed but perhaps he is telling stories to my Bruno up above. It is a comforting thought that life may be simple and yet splendid.

LikeLike

That’s a sweet thought…so very true..life does have its intricacies and simplicities.

LikeLike

I think so too:)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely amazing, my friend… A documented post which I found truly interesting…

Thank you very much for sharing.

Best wishes and happy week ahead to you, Aquileana 😀

LikeLike

Thank you Aquileana, very happy you liked this article on a fascinating prehistoric beast.

Wishing you a wonderful week too,

Vijay

LikeLike

What a scary beastie!

LikeLike

Haha, I would be extra anxious to run into it under the cover of night. It’s beak looks scarily muscular too! :O

LikeLiked by 1 person

Eeek! Run away!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just a note: Quetzalcoatlus and other pterosaurs are not dinosaurs, they’re a a seperate clade than dinosuars. Birds aren’t not directly related to pterosaurs but are in fact dinosaurs because they are descendants of theropod dinosaurs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just a little thought about the food chain here. aif these guys had just bent down and lapped up those pesky roaches that not only survived back then but are still plaguing modern man they might be around today and the roach might be extinct! Of course if modern man would just get some peppermint oil and use it liberally they could make it so uncomfortable for the roaches who hate the smell of the peppermint oil that they would make a forced march to the nearest place to commit mass hari kari and we would be rid of them that way. Simple, probably too simple.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hehehe….

Oh dear, roaches. They truly are a pain. My house has only just recovered from a roach infestation. If they return, I might have to try the peppermint oil thing. Thanks for your comment and for following the blog too. I hope you have a wonderful week! 🙂

Vijay

LikeLiked by 2 people

Don’t wait for them to return – put that oil out NOW! The eggs are there waiting to hatch. Those critters have been around forever cause we mere humans underestimate ’em. Ten dollar investment from Amazon.com, some cotton balls, POOF! No more roaches. They really HATE THE SMELL OF PEPPERMINT OIL. Tell your friends, tell your enemies, tell your mother-in-law! Start a campaign to rid the universe of roaches forever.

You have a wonderful week also. I love humor in all forms.

LikeLiked by 2 people